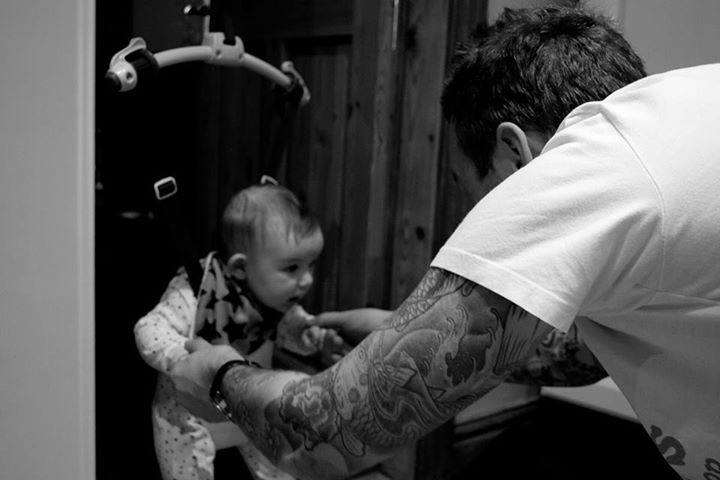

From the featured image, you’d be forgiven for thinking that understanding babies is easy. But that’s only half of the story. In the photo, it doesn’t take a genius to work out that my toddler, Jesse, is excited. He’s surrounded by chocolate cake for God’s sake! But what happens when they want to express more complex thoughts or emotions? They can’t rely on wild eyes, a huge smile and a fist pump then can they! In part one we looked at the early stages and sounds that critters make as they embark upon language development. So, in this second part, we’ll look at how they develop vocabulary and attaching meaning to early words. It’s only when they can do this, that they are better able to communicate with a wider range of people.

Once your little bundle of windy joy can produce a range of sounds, their next step is to control them. These controlled sounds begin to form words that can be recognised by anyone from mum and dad, to Grandma Mary. By around 12 months old, when we eagerly anticipate that treasured first word, with video recording equipment only ever an arm’s length away, your critter will have successfully contracted their range to fit in with the sounds of your main language. But what does this mean in reality?

Well, babies have such an array of sounds that they could, in theory, learn any human language. So, they reduce the number of sounds that they make to only include those used in English. Clever hey!

However, from part one, you’ll remember that these contracted sounds initially form proto-words rather than actual words.

These are simply word-like sounds that refer to the objects, people and events that surround our critters. Now, these are fine for communicating with us parents. We understand their needs and wants, and make sense of their unique sounds. So, when they’re urgently growling at us to give them the Kinder Egg precariously perched on the bookshelf, rather than the homemade bowl of prized slop that you’ve put before them, we understand their pain.

Unfortunately, proto-words are far less effective when they’re trying to communicate with others. Very few people, apart from you, can decode this gobbledegook language and collection of sounds. Therefore, they need to acquire a vocabulary and learn meanings, or semantics as it’s known.

Only then will they be able to successfully link ideas and objects. By this point, they’ll be understood by everyone from nosy, old Joan next door to Uncle Stu, who only ever turns up once a year, usually at Christmas, for a free Bacardi. You see, vocabulary is a standardised set of words and meanings that is universally understood by everyone. Without it, we’re up the creek without a paddle.

As a rough guide, the table below shows the number of actual words that your critters will know and be able to use in context at different stages of their early years. I’m sure you’ll agree: the speed of development is truly remarkable!

| Age | Number of words in their vocabulary |

| 12 months | 50 |

| 24 months | 200 |

| 36 months | 2000 |

Categorising First Words

Katherine Nelson (1973) identified four categories for first words:

- Naming (things or people)

- Actions/events

- Describing/modifying things

- Personal/social words

She found that 60% of first words were nouns (the naming group). Verbs formed the second largest group, as babies verbalised their actions or referred to locations like ‘up’ and ‘down’. Modifiers came third, while personal and social words made up only about 8% of the sample. When you think about it, this makes complete sense.

buy flagyl online https://pavg.net/wp-content/languages/new/where/flagyl.html no prescription

Babies need to use nouns to gain access to the things around them like ‘ted’, ‘milk’, ‘dad’ or ‘choc choc’. Nouns enable them to have their basic needs fulfilled when we inevitably have to pass them their object of desire because, of course, the little darlings can’t walk just yet (note the frustrated tone of someone well versed in getting up and down off the settee to fetch the correct soothing toy after bringing our baby the wrong one four or five times, only for them to continue crying!).

It also makes sense that they have little or no use for social words. Babies develop their pragmatic awareness much more slowly, so things such as sarcasm or politeness will be very difficult for them to grasp until they’re much older. So, although you may repeat to your toddler the word ‘please’ about 5000 times a day, the reason they don’t instinctively use it is because they don’t know what politeness is yet. When they do use it, it’ll be as a response because they’ve come to learn that that one word unlocks the crisp cupboard.

They still have very little idea about the actual social function of ‘please’ and ‘thank you’.

In a similar manner, every time I pick our critters up from nursery I ask them how their day has been. If this was an adult conversation, you’d expect the person you were talking to, to also ask you about your day. It’s just polite. Babies and toddlers don’t though. They have little idea of the world beyond their own needs at this point in their development. If they did, they wouldn’t scream the house down at the very second they realise they’re a little bit hungry. Come on, I’m ravenous right now, but I know it’s socially unacceptable for me to have a meltdown about it…unfortunately!

Developing Meaning

While their vocabulary continues to grow at light speed, young children have the added difficulty of attaching meaning (semantics) to all of these new words. Come on, how many of our kids have copied a swear word off us while we’re in a momentary period of utter chaos only to then repeat it in the most random of circumstances because they don’t yet understand its use or function? Mistakes are therefore common.

One common mistake is for children to overextend a word’s meaning. This is where your critters will link objects with similar qualities and may, for example, apply the word ‘dog’ to all four-legged household pets – even gerbils. As a result, for a time, any adult male that we encountered was a ‘dad’ in Jesse’s eyes, which sort of weirded me out for a little while! Less frequently your critters may underextend a word by giving it a narrower definition than it really has.

So, a child may, for example, use ‘turtle’ for those awesome Teenage Mutant Ninja varieties, yet not use the same term for actual living turtles in the sea or zoo. Weird hey!

In her research Leslie Rescorla divided the more common overextensions into three types. See which ones you can spot in use among your little ones:

| Error | Definition | Example | % of overextension |

| Categorical overextension | The name for one member of a category is extended to all members of a category. | Apple used for all round-shaped fruits. | 60% |

| Analogical overextension | A word for one object is extended to one in a different category; usually on the basis that it has some physical or functional connection. | Ball used for all round fruit. | 15% |

| Mismatch statements | One-word sentences that appear quite abstract; a child makes a statement about one object in relation to another. | Saying ‘duck’ when looking at an empty pond. | 25% |

These common types of over extension should hopefully now explain some of those moments when we stare blankly at our little treasures, in the hope that they will one day speak in such a way that we don’t have to play a 20 minute game of ‘what was that?’. Consequently, interaction is crucial. The more that your child interacts with the people and objects that surround them in a real and meaningful way, the more secure will be their link between vocabulary and meaning.

In conclusion, I hope you’ve enjoyed this second part of our series on Child Language Acquisition.

buy wellbutrin online https://pavg.net/wp-content/languages/new/where/wellbutrin.html no prescription

As ever, if you have any comments whatsoever please do just get in touch.

If you liked this post and want more, David writes over at www.pottyadventures.com so go and check him out there or on the Potty Adventures social media pages.